Finding a common link between Sociological and political views Jacque Fresco's and the Zeitgeist movement ( 2006-2016 ) had, compared to The Keshe Foundation ideas, ideals and projects.

181 by Jedi Simon and other authors. Didactical article. I thank all the authors that made this work possible. I will publish here the results of the findings, concerning the feeling I had some days ago, that all this has already happened, in a slightly different way, but nevertheless, one that could have generated the position and structural thought configuration of the Keshe Foundation.

Jacque Fresco, Futurist Who Envisioned a Society Without Money, Died at 101. He envisioned an alternative society where money would be eliminated and resources distributed equitably ( by computers ). Mr. Fresco created the Venus Project in 1980 to pursue his quixotic plan: creating a resource-based economy that would rescue modern society from the ills of failed political systems. “I would like to see an end to war, poverty and unnecessary human suffering,” he said in an interview. Fresco wrote about sustainable cities, energy efficiency, natural-resource management, cybernetic technology, automation, and the role of science in society. Fresco worked at Douglas Aircraft Company in California during the late 1930s. He presented designs including a flying wing and a disk-shaped aircraft. Grønborg has labeled other facets of Fresco's ideology a "tabula rasa approach". His cybernation governance concept would change the world in his thoughts.

Eliminating Money, Taxes, and Ownership Will Bring Forth Technoutopia. He supported an open system where everything is free and equal, and even open borders. Finland recently began an experiment with universal basic income. And across the continents, other communities run various forms of alternative government, such as the Mareki community on the island of Vanuatu, which doesn't use money or have ownership—everything is community based. He claimed our global monetary economic system and this is going to get super ugly unless we make the biggest paradigm shift in human history. The Venus Project advocated a complete replacement of the current monetary economic system with a “resource based economy”.

Sustainable state of dynamic equilibrium was one of the operative concepts he was working with. This new system aims to de-enslave humanity using technology to provide for the complete needs of our human species based on the carrying capacity of mother earth. In short, they believe that we can utilize technology to manage our resources for the abudant benefit of all of us, not just some us. That means no police needed, no armies, no wars, no wage slave jobs……. As it stands, we are now in mass conflict and the darn thing is failing us. He did not agree with the Bilderberger Group believes who want a one world government based on their monetary system. To better manage the resources and economy they aim to depopulate the world and get it to what they believe is the optimum equilibrium; around 500 million people – their people. Again, as we can see, a glabalization proposal based on interference.

On July 17th, 2016 The Venus Project founder Jacque Fresco received the award for City Design & Community from the NOVUS summit in conjunction with the United Nations division UN DESA. United nations in fact hold annual summits to help humanitarian, governmental and non-governmental organizations, showcasing innovations for sustainable development to transform the world in a positive way, being right there where change could take place, to organize it, unite humanity towards a better future for all, and certainly divert vectors that are non aligned to their wishes and thoughts. Manufacturing Dissent, is another field of the propaganda model controlled or exported by UN, apparently. Globalization and New World Order, always come together, and every time you shall meet the concept of Glo Baal ization, do not forget that it is a very ancient dream some might still wanto to carry out, in some way or another. Legitimation and consensus, granted, as well as help, logistics to manifacture a social engineered society that meets the need of the few. Wells’ prognostication was, without a doubt, correct. As the global government envisioned by the supranational elite is gradually instantiated, many voices of dissent will be raised and subsequently eradicated. Yet, not every dissenter may “die protesting against it,” but will die unwittingly embracing it instead.

Some dissenters may, in fact, naively accept another form of global government being proffered as a viable alternative. Such is the case with Zeitgeist: Addendum. Zeitgeist either intentionally or unwittingly failed to recognize the problems for what they were: contrived grievances employed as polar extremes to perpetuate a dialectical climate. Speculation, posed within a distinctly Hegelian framework. Addendum portrayed the problems as the natural outgrowths of America’s constitutional republican system, thereby vilifying representative democracy and enshrining the technocratic paradigm. You might force some kind of technological innovation into society, but intent will show sooner or later.

The notion that social progress is inextricably linked to scientific and technological progress, is an old one. Such a contention is vintage techno-Utopianism, the belief that technology will eventually end all social evils and give rise to a perfect society. Techno-Utopianism was an outgrowth of the Enlightenment, a reality underscored by one of its theoretical progenitors: Henri de Saint-Simon. In turn, the Enlightenment was an outgrowth of older occult religions. Every form of scientific totalitarianism that would emerge in the 20th century was inspired by the revolutionary faith that percolated beneath the surface of the Enlightenment. Just another variant of the ruling elite’s Weltanschauung.

To understand the societal model being promoted by Zeitgeist: Addendum, one must examine the development of the revolutionary faith that inspired all modern sociopolitical Utopian movements. The film’s techno-Utopian premises are derivative of this faith and, as such, can only promise the same results. Just as Zeitgeist: Addendum’s political doctrine is inextricably linked to a corresponding neo-pagan spirituality, so was the revolutionary faith inextricably linked to ancient occult religions. One cannot help but notice the virulent derision for traditional religions, namely Christianity, that is espoused throughout the course of Zeitgeist: Addendum. The film echoes the same tired anti-Christian rhetoric of Karl Marx augmented by the historically bankrupt Christ-myth conspiracy theory of Achayra S (which merely recycles the thoroughly refuted thesis of Kersey Graves’ The World’s Sixteen Crucified Saviors).

Simultaneously, the movie presents a hodgepodge of Theosophical, Gnostic, astrotheological, and New Age ideas as a viable new world religion. Such an occult counterculture model is similar to the early anti-theistic sociopolitical Utopian movements that were spawned by the Enlightenment. It is with Gnosticism that one finds the proximate origins of sociopolitical Utopianism. The Gnostic trappings of early sociopolitical Utopian movements are demonstrable in the various ideas promoted by Enlightenment luminaries. One case in point is Condorcet’s “doctrine of a coming Utopia, where indefinite progress would bring forth a ‘natural salvation’ of plenty and immortality” (Goeringer, “The Enlightenment, Freemasonry, and the Illuminati”). Condorcet’s doctrine of “natural salvation” merely reiterated the Gnostic doctrine of self-salvation.

This veneration of the Devil under his original angelic title constituted the religion of Luciferianism. Like some varieties of Satanism, Luciferianism did not depict the devil as a literal metaphysical entity. Lucifer only symbolized the cognitive powers of man. He was the embodiment of science and reason. It was the Luciferian’s religious conviction that these two facilitative forces would dethrone the “superstitious” institutions of God and apotheosize man. This re-conceptualization of Lucifer reiterated the theme of Gnostic immanentization. Lucifer, whom traditional Christianity regards as a spiritual entity, was rendered purely immanent.

Now, Lucifer was ontologically transplanted within the human mind, which Enlightenment adherents believed to be a purely corporeal entity. Indeed, the only logical conclusion that a secular humanist can arrive at is that man is becoming god. It is interesting to note that Diderot, who was ostensibly an atheist, would select religious personages such as Lucifer to adorn his “compendium of human knowledge.” Diderot’s appropriation of the “symbol of light and rebellion” as a core icon for the title page of Encyclopedia suggests a conception of human knowledge that parallels the fallen angel’s hubristic belief that he would make himself “like the Most High” (Isaiah 14:14). Atheism provides the philosophical segue for the enthronement of man as the Most High. This enthronement begins with the recognition of a logical contradiction inherent to atheism.

It is philosophically impossible to be an atheist, since to be an atheist you must have infinite knowledge in order to know absolutely that there is no God. But to have infinite knowledge, you would have to be God yourself. It’s hard to be God yourself and an atheist at the same time! Nineteenth-and early twentieth-century thought teems with time-bound emergent deities. Scores of thinkers preached some sort of faith in what is potential in time, in place of the traditional Christian and mystical faith in a power outside of time. Hegel’s Weltgeist, Comte’s Humanite, Spencer’s organismic humanity inevitably improving itself by the laws of evolution, Nietzsche’s doctrine of superhumanity, the conception of a finite God given currency by J.S. Mill, Hastings Rashdall, and William James, the vitalism of Bergson and Shaw, the emergent evolutionism of Samuel Alexander and Lloyd Morgan, the theories of divine immanence in the liberal movement in Protestant theology, and du Nouy’s telefinalism–all are exhibits in evidence of the influence chiefly of evolutionary thinking, both before and after Darwin, in Western intellectual history.

The faith of progress itself–especially the idea of progress as built into the evolutionary scheme of things-is in every way the psychological equivalent of religion. There is one invariant feature within this long ideational chain: a religious veneration for “progress” itself. In fact, the terms “evolution” and “progress” can be used interchangeably. Expanding on the religion of progress and its numerous permutations. Darwinism’s most significant extrapolation was the extension of evolutionary principles from biology to political science. In the context of governance, the final outcome of evolution would be a politically and economically interdependent world.

There have been several appellations assigned to such a global sociopolitical arrangement. As Coomaraswamy previously stated, Kant called this arrangement a “Universal civil society.” H.G. Wells called it the “New Republic.” Adolf Hitler called it the “Third Reich.” Neoconservative ideologues have called it Pax Americana. Internationalists of the more Eurocentric ilk have called it Pax Europa. Most notably, George Herbert Walker Bush popularized the concept under the appellation of a “New World Order.” These various monikers aside, every movement that has attempted to establish a system of political and economic interdependence has invariably enshrined the same form of governance: a global socialist totalitarian state. From their evolutionary perspective, such a world order would be the natural corollary of man’s alleged political evolution.

In this sense, the globalist, whether of the Transnationalist and Internationalist variety, qualifies as a “sociopolitical Darwinist. Both of these globalist groups operate on the same fundamental assumptions about the meaning of human society today. Both agree on the face of it that the most important single trait that pervades the life of all nations is interdependence. And both agree that interdependence is a progressive function of evolutionary progress. Evolutionary, as in Darwin. In practical terms, both of these groups operate on the same working assumption Charles Darwin arbitrarily adopted to rationalize his feelings about mankind’s physical origins and history. If it worked so well for Darwin, they almost seem to say, why not expand the idea of orderly progress through natural evolution to include such sociopolitical arrangements as corporations and nations? In this view, the most useful of Darwin’s concepts is that of human existence as essentially a struggle in which the weakest perish, the fittest survive and the strongest flourish.

When applied to sociopolitical arrangements, this Darwinist process seems almost to dictate the Internationalist and Transnationalist one-world view of things. The continuing clash and contention in the world as it has been until now has resulted in a slow evolution of those who have survived from one stage of interdependent order to another. From time to time, natural “catastrophes” have intervened, forcing “nature” to take another path. But at each new stage, interdependence has become more important and more complex. The greater the interdependence between groups, the higher the evolutionary stage, the more the balance achieved between interdependent groups results in the common good.

The view of the Internationalists and Transnationalists is that they are the ones who are equipped to bring mankind to the highest level of the sociopolitical evolution. Their effort is to bring together into one harmonious whole all those separate parts of our world that have not yet “evolved” into a natural cohesion for the common good. A global government is merely the political expression of the metaphysical monism that originated with Gnosticism and the ancient Mystery religions.

The Enlightenment provided the conceptual and philosophical segue for the transposition of metaphysical monism into a sociopolitical context. Whether the globalist realizes it or not, their mandate to create “one world” merely reiterates the occult contention that “all is one.” While many sociopolitical Utopians (e.g., Marxists, secular humanists, communists, fascists, etc.) relegate texts such as the Biblical Eden account to mere myth, an Edenic motif remains firmly embedded within their own Weltanschauung. In the beginning of this secular mythology, Eden was a singularity, which was eventually divided into countless pluralities by the Big Bang.

According to the myth, the reconstitution of Eden is achieved through evolution, which invariably requires the assistance of Man (spelled with a capital M to signify humanity’s potential to achieve apotheosis through the evolutionary process). Man unites evolution with the science of “progress,” which is bodied forth through biological methodologies (e.g., eugenics, population control, etc.) and social methodologies (e.g., communism, fascism, and other forms of sociopolitical Utopianism). As evolution is guided down the desired course, Man returns to the singularity (i.e., a world government and a unified consciousness). Thus, Eden is reborn. However, Eden is confined to this ontological plane and immortality is attainable only through the continuity of the species. If elements of this mythology sound familiar, it is because it is certainly nothing new. It is derivative of ancient occult cosmologies, particularly Gnosticism. The only difference is that the scientistic version stipulates an Eschaton residing entirely within this physical universe.

The extrapolation of occult concepts into revolutionary doctrine produced a new Gnosticism that envisaged the manifestation of the Eschaton within the immanent cosmos. Commenting on this new strain of Gnosticism, Wolfgang Smith writes:

In place of an Eschaton which ontologically transcends the confines of this world, the modern Gnostic envisions an End within history, an Eschaton, therefore, which is to be realized within the ontological plane of this visible universe.

The Enlightenment would reach its violent nadir with the bloody French Revolution, which would provide the blueprint for all modern socialist revolutions. Communism, fascism, and other competing forms of socialism proffer a heaven on earth. In this sense, all modern socialist revolutionaries qualify as secular Gnostics:

In this century, with the presentation of traditional religious positions in secular form, there has emerged a secular Gnosticism beside the other great secular religions–the mystical union of Fascism, the apocalypse of Marxist dialectic, the Earthly City of social democracy. The secular Gnosticism is almost never recognized for what it is, and it can exist alongside other convictions almost unperceived.

The codification of Gnosticism as revolutionary doctrine produced secular movements that, sociologically, behaved like religious movements. The religious character of these secular movements is made evident by the “new reality” that they sought to tangibly enact. James H. Billington describes this “new reality”:

The new reality they sought was radically secular and stridently simple. The ideal was not the balanced complexity of the new American federation, but the occult simplicity of its great seal: an all-seeing eye atop a pyramid over the words Novus Ordo Seclorum. In search of primal, natural truths, revolutionaries looked back to pre-Christian antiquity–adopting pagan names like “Anaxagoras” Chaumette and “Anacharsis” Cloots, idealizing above all the semimythic Pythagoras as the model intellect-turned-revolutionary and the Pythagorean belief in prime numbers, geometric forms, and the higher harmonies of music.

It is very interesting that such a “radically secular” reality would be so preoccupied with the “occult simplicity” and “pagan names” of “pre-Christian antiquity.” Yet, as sociologist William Sims Bainbridge observes, such occult proclivities are the natural corollaries of secularism:

Secularization does not mean a decline in the need for religion, but only a loss of power by traditional denominations. Studies of the geography of religion show that where the churches become weak, cults and occultism explode to fill the spiritual vacuum. (“Religions for a Galactic Civilization”)

Indeed, occultism did explode to fill the power vacuum once occupied by traditional ecclesiastical authorities. One of the occult personages that would remain as a fixture of the early revolutionary faith was Lucifer. However, he would assume yet another title. The term Lucifer, as translated by St. Jerome from the original Hebrew Helel (“bright one”), shares the same meaning as Prometheus who brought fire to humanity (“Lucifer,” Answers.com). The mythical character of Prometheus was central to the Utopian vision of early socialist revolutionaries. James H. Billington explains:

A recurrent mythic theme for revolutionaries — early romantics, the young Marx, the Russians of Lenin’s time — was Prometheus, who stole fire from the gods for the use of mankind. The Promethean faith of revolutionaries resembled in many respects the general belief that science would lead men out of darkness into light.

The Promethean contention that science was the lantern guiding man to illumination was vintage scientism. Scientism, which should not be confused with legitimate science, is the belief that the investigational methods of science are essential to all other fields of study. The modern mind, chronocentric as it is, might view such epistemological imperialism as desirable. However, as a system of quantification, science can only concern itself with quantifiable entities. Such epistemological rigidity allows for the potential preclusion of important data. Michael Hoffman reiterates:

The reason that science is a bad master and dangerous servant and ought not to be worshipped is that science is not objective. Science is fundamentally about the uses of measurement. What does not fit the yardstick of the scientist is discarded. Scientific determinism has repeatedly excluded some data from its measurement and fudged other data, such as Piltdown Man, in order to support the self-fulfilling nature of its own agenda, be it Darwinism or “cut, burn and poison” methods of cancer “treatment.”

When applied to questions of governance, science invariably becomes an oppressor. Because they defy quantification, concepts like human dignity and liberty are precluded from a purely scientific interpretation of governance. In the absence of concepts like liberty and dignity, otherwise questionable policies can be scientifically dignified with no regard given to moral considerations. Such was the case with Nazi Germany, the perennial model of eugenical regimentation. It is ironic that scientism, which devalues human life, was at the core of the Promethean revolutionaries’ anthropocentric faith. In the end, Promethean revolutionaries murdered countless members of the very species that they sought to apotheosize: man. Hoffman synopsizes the logical ends of scientism:

The doctrine of man playing god reaches its nadir in the philosophy of scientism which makes possible the complete mental, spiritual and physical enslavement of mankind through technologies such as satellite and computer surveillance; a state of affairs symbolized by the “All Seeing Eye” above the unfinished pyramid on the U.S. one dollar bill.

Nevertheless, the scientistic approach to governance was a hallmark of the Promethean revolutionaries. Friedrich Engels described Marx’s theory as “scientific socialism” because both science and Marxism bestowed epistemological primacy upon observable phenomenon (“Scientific socialism,” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia). Marx’s emphasis upon radical empiricism was presaged by Henri Saint-Simon’s physiological interpretation of the state, which extended the doctrine of sense certainty “into the altogether new field of social relations” (Billington 212). Adherents of Saint-Simon’s philosophy contended that “the key to diagnosing and curing the ills of humanity lay in an objective understanding of the physiological realities that lay behind all thinking and feeling” (212). Following this physiological interpretation of governance to its logical ends, Saint-Simon developed the precursor to Marx’s “scientific socialism”:

Believing that the scientific method should be applied to the body of society as well as to the individual body, Saint-Simon proceeded to analyze society in terms of its physiological components: classes. He never conceived of economic classes in the Marxian sense, but his functional class analysis prepared the way for Marx.

Thus, radical empiricism provides the epistemological basis for all modern forms of scientific totalitarianism. It is also with radical empiricism that one finds another occult element of sociopolitical Utopianism. This epistemology stems from the Gnostic derision of cognitio fidei (the cognition of faith). Moreover, radical empiricism arrives at conclusions that are inescapably mystical in character. An exclusively empirical approach relegates cause to the realm of metaphysical fantasy. This holds enormous ramifications for science. What is perceived as A causing B could be merely a consequence of circumstantial juxtaposition. Although temporal succession and spatial proximity are axiomatic, causal connection is not. Affirmation of causal relationships is impossible. Given the absence of causality, all of a scientist’s findings must be taken upon faith. Ironically, science relies on the affirmation of such cause and effect relationships.

Saint-Simon’s work has been described as the prescription for Sir Francis Bacon’s prophetic vision of a technocratic society (Fischer 69). Technocratic governance, or Technocracy, is a governmental system where scientists and technicians act as the sole decision-making body. This inherently anti-democratic concept originated within esoteric circles. Sir Francis Bacon developed the original model for Technocracy in his book, The New Atlantis. Published in 1627, The New Atlantis was adorned with the symbols of occult Freemasonry and presented the Rosicrucian mandate for the formation of an “Invisible College” (Howard 74-75). Bacon himself was a member of the secret Order of the Helmet and, some allege, a Grand Master of the secret Rosicrucian Order (74). The Utopia presented by Bacon in The New Atlantis was “a pure Technocratic society” (Fischer 66-67). The philosopher kings of Plato’s Republic were to be replaced by a “technical elite” (66-67). Scientists and technicians would circumvent conflicting political interests, giving rise to an apolitical bureaucracy.

Technocratic ideas constituted a portion of the conceptual and philosophical foundation for modern socialist totalitarian governance. Of course, a majority of socialist totalitarian regimes that have populated modernity have been overtly hostile towards theistic faiths, particularly Christianity. This derision for theistic faiths is attributable to the characteristic scientism of technocratic theory. Because the soul, angels, demons, and God Himself are neither quantifiably or empirically demonstrable entities, they have no place within a technocratic society. Science becomes the new expositor of miracles, revelation, and truth. In Brave New World Revisited, Aldous Huxley described this scientistic form of governance:

The older dictators fell because they could never supply their subjects with enough bread, enough circuses, enough miracles, and mysteries. Under a scientific dictatorship, education will really work with the result that most men and women will grow up to love their servitude and will never dream of revolution. There seems to be no good reason why a thoroughly scientific dictatorship should ever be overthrown.

Wielding ostensible epistemic primacy, the “experts” of Technocracy employ the gnosis of science to produce “enough bread, enough circuses, enough miracles, and mysteries” for their subjects. Distracted by all of the comforts that technology can supply, most men and women would never dream of revolting against the new theocracy of science. This is precisely the same sort of society mandated by Zeitgeist: Addendum, a reality underscored by the film’s promotion of the ideas of Jacque Fresco.

Jacque Fresco: Proselyte of the Global Technocratic State

The technocratic nature of Zeitgeist: Addendum’s prescription is made evident by one of the ideologues interviewed in the film: Jacque Fresco. In hopes of realizing his techno-Utopian vision for the world, Fresco founded the Venus Project in 1975 (“The Venus Project,” Living on Purpose). Zeitgeist: Addendum is essentially a commercial for Fresco’s Venus Project.

Fresco appears throughout the movie, intermittently espousing ridiculously quixotic Utopian romanticist doctrines and reiterating the same tired anti-theist polemics that have already been refuted by many reputable Christian apologists. All of his pseudo-intellectual rhetoric aside, Fresco is nothing more than an anti-American technophile suffering from Promethean hubris. Unfortunately, the more credulous audiences that have adopted the technocratic gospel of Zeitgeist: Addendum cannot identify the dubious strands of thought that underpin many of Fresco’s assertions. For instance, at one point, Fresco states:

“Now, America is inclined toward fascism. It has a propensity, by its dominant philosophy and religion, to uphold the fascist point of view. American industry is essentially a fascist institution. If you don’t understand that, the minute you punch that time clock, you walk into a dictatorship.” (Zeitgeist: Addendum)

Fresco is only partially correct. While there is little doubt that there are fascist elements entrenched in present-day America, these elements are extraneous. They did not originate with Americanism, but gradually co-opted the institution after its inception. Fresco is either intentionally or unwittingly confusing Americanism with corporatism. Americanism promotes free market capitalism. Corporatism, which is synonymous with fascism, promotes monopolistic capitalism. By wedding the government to private business interests, the corporatist state enables monopolistic capitalists to consolidate and control the means of production. Meanwhile, smaller businesses are expunged from the marketplace through rigid governmental regulation.

Thus, Fresco presents humanity’s choices of government within a distinctly Hegelian framework. By positing that Americanism is inherently fascistic, Fresco is either intentionally or unwittingly encouraging audiences to gravitate closer towards the other dialectical extreme: communism. Yet, the dialectical commonalities of fascism and communism are overwhelmingly transparent, a reality that is demonstrable in the etymology of the two systems themselves. The appellation of “communism” comes from the Latin root communis, which means “group” living. Fascism is a derivation of the Italian word fascio, which is translated as “bundle” or “group.” Both fascism and communism are forms of coercive group living, or more succinctly, collectivism.

The only substantial difference between these dialectical extremes is fascism’s limited observance of private property rights, which is superficial at best given its susceptibility to rigid governmental regulation. In 1933, Hitler candidly admitted to Hermann Rauschning that “the whole of National Socialism is based on Marx” (Martin 239). Indeed, Nazism (a variant of fascism) is derivative of Marxism. Monopolistic capitalists like Rockefeller financed the rise of communism because they correctly identified it as the quintessential monopoly. In essence, communism is a system of monopolistic capitalism where the omnipotent State acts as an ersatz corporation. In practice, fascism was merely Marxism with the added pageantry of ostensible private ownership. The historical conflicts between communism and fascism were merely feuds between two socialist totalitarian camps, not two dichotomously related forces.

Nevertheless, by confusing Americanism with fascism, Fresco automatically ensnares more credulous audiences within a dialectical trap. Ayn Rand synopsizes this dialectical trap as follows:

It is obvious what the fraudulent issue of fascism versus communism accomplishes: it sets up, as opposites, two variants of the same political system… it switches the choice of “Freedom or dictatorship?” into “Which kind of dictatorship?”–thus establishing dictatorship as an inevitable fact and offering only a choice of rulers. The choice–according to the proponents of the fraud – is: a dictatorship of the rich (fascism) or a dictatorship of the poor (communism).

Fresco’s anti-capitalist rhetoric betrays his technocratic pedigree. Although Fresco rejects the appellation of “technocrat,” he was a member of Technocracy Incorporated for many years (“Jacque Fresco,” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia). Fresco’s technocratic propensities become all the more apparent when one examines his promotion of a “resource-based economy” (ibid). Such an economic model was also promoted by Harold Loeb, a technocrat who believed that unfettered technological progress would eventually end scarcity and supplant capitalism with a techno-Utopian system of governance. In Life in a Technocracy, Loeb states:

Men live by the production, distribution, and consumption of goods. Goods are produced and distributed by effort. The incentive of effort is profit. Profit depends on price. Price depends on scarcity. Therefore, the life of man under the capitalist system, depends on the scarcity of goods. And the scarcity of goods is being progressively destroyed by the application of science to production, known in its latest phase as technology. (7; emphasis added)

While some of Loeb’s criticisms of scarcity-based economics are valid, his assumption that such an economic model was automatically synonymous with America’s free market economy is incorrect. Nevertheless, technocrats like Loeb forthrightly condemned Americanism. In fact, many sects of the early technocratic movement were “anticapitalistic and revolutionary in their rhetoric” (Akin 82). Some technocrats even “mingled socialism, managerialism, and assorted beliefs” (83). William Akin further reveals the Marxian proclivities of the early technocratic movement:

In California, adherents visualized an efficient totalitarian society in which “the individual must subordinate himself to the community” and which would function automatically under the guidance of engineers. The American Technocratic League of Denver was openly socialist. From Chicago the All American Technological Society proposed the use of the Soviet Union as a model for the new order. (83)

Such technocratic enclaves provide a fragmentary glimpse of Fresco’s true ideological heritage. Like Loeb, Fresco believes that technology will eventually end scarcity, thereby relegating capitalism to obsolescence. Throughout the course of Zeitgeist: Addendum, Fresco consistently characterizes profit as the natural correlative of greed. Apart from the fact that such an association is a hastily formulated oversimplification, Fresco’s virulent derision of profit takes on a technocratic dimension when examined in conjunction with his conviction that technology will end scarcity and capitalism with it.

While Fresco claims that he does not advocate communism, he speaks about the system with a great deal of affinity. During an interview on Living on Purpose, Fresco reminisces fondly about the various flirtations with communism that took place during the Great Depression:

During the Depression, everybody was looking for new ways. That’s amazing. Communism, socialism were up on soapboxes. The Secretary of State of the United States went to Russia to see what they were doing and he liked what they were doing. So, they made a film called Mission to Moscow… It ran in this country. Very successful. Favorable to communism. Of course, all of that was taken away. It’s gone now. You can’t even see it anywhere. And, I don’t say that it’s good or bad, but that was good. It was more of an open system. (“The Venus Project,” Living on Purpose)

Fresco’s one major criticism of communism and socialism seems to be the fact that these systems, like all other world systems, employ a monetary-based economy (“What is The Venus Project”). Like Loeb, Fresco contends that monetary systems invariably lead to scarcity (ibid). Fresco contends that, in turn, scarcity is the crucible of all social evils, including “social stratification, elitism, nationalism, and racism” (ibid). Thus, it would appear that Fresco’s only major misgivings with communism and socialism are those systems’ reliance upon monetary-based economic models.

The solution, according to Fresco, is the instantiation of a cashless society:

“Today we have access to highly advanced technologies. But our social and economic system has not kept up with our technological capabilities that could easily create a world of abundance, free of servitude and debt. This could be accomplished with the infusion of a global, resource-based civilization where all goods and services are available without the use of money, credit, barter or any other form of debt or servitude.” (Qutd. in Noni Durrani. “Jacque Fresco On The Future”)

Yet, such a non-monetary system was a hallmark of the stateless socialism envisioned by some variants of Marxism. Arguably, money was virtually nonexistent in some Marxist regimes, such as Cambodia under the genocidal Khmer Rouge. In Maoist China and the Soviet Union, money played an ancillary role at best. Within these regimes, neither productive resources nor a share of production itself could be acquired through the issuance of liabilities. Thus, communist and socialist economies could be considered mere segues for the instantiation of non-monetary systems.

Ominously enough, a cashless society has also been the objective of some of the globalist interests that financed the rise of communism. Why? In a cashless society, there is a distinct lack of financial privacy. In the absence of that privacy, the state can arbitrarily confiscate the wealth of the lower and middle classes. Fresco believes that such universal financial transparency would obliterate elitism and social stratification. Yet, historically, the ruling elite have always found ways to conceal their financial information, even in the most economically regimented societies.

In the United States, for instance, the wealthy have been able to conceal their financial information through offshore banking schemes, shell games, and loopholes governing cash transaction reports. As a result, untold billions of dollars connected to the international drug trade and terrorism have passed through the hands of elites. In a cashless society, whatever is deemed credit can and most likely will be regulated in a similar fashion. A cashless system would precede the growth of a huge black market and guerilla economy as criminal infrastructures develop new and creative ways to circumvent financial transparency. Historically, the global oligarchical establishment has maintained close ties to the criminal underworld. This reality reduces the notion of financial equality to a pipe dream of the first order.

Moreover, Fresco’s contention that all social evils are inextricably linked to monetary-based economies is inherently fallacious. How does Fresco account for all the instances of “social stratification, elitism, nationalism, and racism” that preceded the advent of any monetary-based economies? Evidently, the inherent nature of man is plagued by a systemic corruption that existed before money. Ironically, his reality is affirmed by Biblical Christianity, a Weltanschauung that Fresco categorically rejects. In 1 Timothy 6:10, the apostle Paul makes it clear that it is the “love of money,” not money itself, that is the root of all evils. In the absence of money, man will simply find something else to worship. In the case of Fresco, he has chosen to worship the cognitive powers of man. Fresco venerates science and technology, which are the products of human intellect. For Fresco, science and technology are the instruments by which man shall reconstitute Eden without God. Such a contention merely reiterates the mantra of an older anthropocentric religion: “Ye shall be as gods.” Herein is the true motive for Fresco’s anti-theist rhetoric.

Revisiting Walden Two: Fresco’s Behavioral Tyranny

Fresco’s contention that monetary-based economies are the source of all social evils pays credence to the behaviorist theory that man is a tabula rasa who is determined exclusively by external forces. In turn, behaviorism is premised on the physicalist philosophy of mind. Physicalism holds that outward behavior is the only adequate indicator of mental states. From the physicalist vantage point, cognition is a purely corporeal process and the soul is a metaphysical fantasy. Working from this premise, Skinner developed a “technology of behavior” by which human nature could be conditioned and manipulated. Skinner believed that, as desirable behaviors were promulgated within the human herd, the ideal society would eventually emerge.

Skinner presented his psychologically engineered Utopia as a roman a’ clef entitled Walden Two. Characterizing Walden Two as an innocuous fiction, Skinner stated: “The ‘behavioral engineering’ I had so frequently mentioned in the book was, at the time, little more than science fiction” (vi). Yet, behavioral engineering was no fiction for one of Skinner’s theoretical forerunners: Adam Weishaupt.

Weishaupt was an Enlightenment thinker and the founder of the infamous Bavarian Illuminati. Working off the physicalist contention that observable behavior was the primary indicator of mental states, Weishaupt developed a method of hierarchical observation called “Seelenspionage,” which means “spying on the soul.” Seelenspionage involved the close observation of Illuminist adepts. Through such observation, Weishaupt believed that the Illuminist hierarchy could:

. . .get access to the adept’s soul by close analysis of the seemingly random gestures, expressions, or words that betrayed the adept’s true feelings. Von Knigge, who was privy to the system, referred to it as a “Semiotik der Seele.” “From the comparisons of all these characteristics,” von Knigge wrote, “even those which seem the smallest and least significant, one draw conclusions which have enormous significance for knowledge of human beings, and gradually draw out of that reliable semiotics of the soul. (Jones 14)

Astute readers will recognize Weishaupt’s Seelenspionage as a precursor to B.F. Skinner’s behaviorism. Like Weishaupt’s system of behavioral observation and modification, Skinner’s behaviorism was premised upon the physicalist assumption that all observable behavior provided the only adequate indicator of “mental states.” In fact, Skinner’s reductionistic metaphysics virtually obliterated the “mental state,” transforming it into a proverbial mirage imposed upon observable behavior by the percipient. Thus, from Skinner’s perspective, man was merely an amalgam of behavioral repertoires that could be manipulated and controlled.

To his credit, Weishaupt identified the semiotic dimension to observable behavior, a reality that later physicalists like Skinner would ignore. However, the very same sort of reductionistic metaphysics to which Skinner and later physicalists would subscribe also plagued Weishaupt’s “semiotics of the soul.” Weishaupt attempted to reduce the extremely complex undercurrent of connotative meaning underpinning observable behavior to a simplistic paint-by-numbers schematic. Such a one-dimensional approach is reminiscent of Delsartes’ method of acting, which contended that truly great performers could mimic all the proper gestures to communicate the emotional state of their characters.

Yet, in spite of its crude and overly simplistic schematicism, this Illuminist variety of behavioral tyranny would find a permanent place in the litany of contemporary totalitarian practices:

In Illuminism we find in seminal form the system of police state spying on its citizens, the essence of psychoanalysis, the rationale for psychological testing, the therapy of journal keeping, the idea of Kinsey’s sex histories, the spontaneous confessions at Communist show trials, Gramsci’s march through the institutions, the manipulation of the sexual passion as a form of control that was the basis for advertising, and, via Comte, the rise of the “science” of behaviorism, which attempts, in the words of John B. Watson, to “predict and control behavior.” (17)

It comes as little surprise that Skinner believed that the system of communism practiced in Red China presented a societal model that America should emulate (Skinner xv). The Illuminist system of “social control” would provide the operational protocol for every totalitarian regime throughout the 20th century. Communism, fascism, and other forms of oligarchical governance have employed some variation of Weishaupt’s panopticism (Jones 17). Ultimately, the goal has always been what Weishaupt called the Maschinenmenschen, a completely mechanized man:

Once released into the intellectual ether, the vision of machine people in a machine state controlled by Jesuit-like scientist controllers would capture the imagination of generations to come, either as utopia in the thinking of people like Auguste Comte or dystopia in the minds of people like Aldous Huxley and Fritz Lang, whose film Metropolis seemed to be Weishaupt’s vision come to life. (Jones 16-17)

The Weishauptian concept of Maschinenmenschen that presaged Skinner’s behaviorist portrait of humanity was also embraced by the technocratic movement:

The technocrats attempted to pull all of these strands–their faith in positivistic science; their mechanistic view of man with his essentially animal-like irrationality, his desire for security, abundance, and tranquility; the organizational imperative caused by natural inequality; and the dominance of technology– together into one functional ideal whole. It resembled Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and the managerial society that James Burnham deplored; it could equally lead to B.F. Skinner’s Walden Two.

Fresco also exhibits such technocratic propensities, as is evidenced by the behaviorist-physicalist portrait of man presented at the Venus Project’s official website. The Venus Project’s organizational biography states: “Experience tells us that human behavior can be modified, either toward constructive or destructive activity” (“What is The Venus Project?”). This contention is reiterated later in the Venus Project’s manifesto:

Human behavior is subject to the same laws as any other natural phenomenon. Our customs, behaviors, and values are byproducts of our culture. No one is born with greed, prejudice, bigotry, patriotism and hatred; these are all learned behavior patterns. If the environment is unaltered, similar behavior will reoccur. (“What is the Venus Project?”)

Such a contention presupposes that man is a tabula rasa awaiting the enlightened brushstrokes of social engineers. After all, if man is determined exclusively by external forces, it stands to reason that his circumstances and conditions must be managed in order to produce the desirable modes of behavior. Whether Fresco realizes it or not, he is providing the rationale for the very “machine state” envisioned by Lang, Huxley, Weishaupt, Comte, and, of course, Skinner. Of such a psychologically engineered society, C.S. Lewis writes:

. . .many a mild-eyed scientist in a democratic laboratory means, in the last resort, just what the Fascist means. He believes that “good” means whatever men are conditioned to approve. He believes that it is the function of him and his kind to condition men; to create consciences by eugenics, psychological manipulation of infants, state education and mass propaganda. Because he is confused, he does not yet fully realize that those who create conscience cannot be subject to conscience themselves. But he must awake to the logic of his position sooner or later; and when he does, what barrier remains between us and the final division of the race into a few conditioners who stand themselves outside morality and the many conditioned in whom such morality as the experts choose is produced at the experts’ pleasure? If “good” means only the local ideology, how can those who invent the local ideology be guided by any idea of good themselves? (81)

Indeed, when they speak of a psychologically engineered society, the “mild-eyed scientist” and the fascist mean exactly the same thing. They mean a socialist totalitarian society where the “many conditioned” are controlled by the “few conditioners.” In short, they mean a scientific dictatorship. Such is the logical outworking of Fresco’s behaviorist contentions. There can be little doubt that such such thinking is a corollary of Fresco’s ideological heritage as a former member of Technocracy Incorporated. Evidently, the apple doesn’t fall too far from the tree.

Mandating a Sedentary World

Throughout the course of Zeitgeist: Addendum, Fresco childishly decries work and labor as corrupting forces that are stultifying man’s alleged evolutionary ascent. Such a contention betrays Fresco’s infantile resentment of productivity. To be sure, not all employers are fair and not all work is legitimate. However, it is a transparent generalization to assert that all work and labor constitute drudgery and servitude. Nevertheless, Zeitgeist: Addendum reiterates this assertion ad nauseam. At one point in the film, Joseph declares:

In a high technology, resource-based economy, it is conservative to say that about 90 percent of all current occupations could be phased out by machines, freeing humans to live their lives without servitude. (Zeitgeist: Addendum)

Again, the technocratic theme of a “machine state” emerges. Apart from being hopelessly quixotic, this statement bespeaks Joseph’s contention that industrialism is the dominant force in the development of social order. Such a contention merely reiterates the outlook of Saint-Simon, who would indoctrinate Comte into technocratic doctrines:

It was from Saint-Simon that Comte got the idea that Industrialism was to be the new form of social order that would replace the old order which had been swept irrevocably away by the revolution. The new order was to be based on science, not the discredited religion, because no one could argue with science, which [Mary] Shelley has said, was based on fact, not hypothesis. “Hypothesi non fingo,” Newton had written, and Shelley had quoted the passage in a footnote to Queen Mab as the marching orders for the New Man who would bring about heaven on earth. (Jones 94)

Such religious veneration of industrialism, technology, and science was at the heart of most sociopolitical Utopian movements. In turn, sociopolitical Utopianism represents the philosophical, ideological, and religious nucleus of all modern socialist totalitarian regimes. Historian Richard J. Sutcliffe states:

In the last hundred years or so, “scientific” views of history have become increasingly popular, for humanity as a statistical whole is thought of as being subject to analysis and prediction. In this thinking, once the motivations of the masses could be measured and tabulated, their response to economic or technological stimuli could be accurately predicted. Appropriate technology and education could then be adapted to engineer and control the desired society. Such theories are popular among both political rightists and leftists, neither of whom realize that they are advocating the same kind of society–a sort of “scientific totalitarianism” or “technocratic dictatorship.” (The Fourth Civilization: Society, Technology, and Ethics)

The promotion of the scientistic approach to governance aside, the vision of a world where work is abolished through automation is fallacious. The introduction of machines in the workplace does not obliterate jobs, but simply creates new ones. After all, who will maintain the machines?

Yet, assuming that the vision of a completely automated workplace is plausible, it is questionable as to whether or not such a world would be desirable. Both Joseph and Fresco contend that automation will “free” man, but that merely raises another question. If man is freed from all work, then what is he free to do? Fresco and Joseph never clearly answer this question. All that they offer is nebulous rhetoric about humanity being free to pursue fuzzy enterprises of self-actualization and self-enrichment.

This response only gives rise to even more questions. Towards what ends would such pursuits be directed? Even if people were free to do nothing else but seek knowledge, the acquisition of that knowledge would prove to be absolutely worthless. Why? The practical application of knowledge is tangibly expressed through work, which will have been supposedly abolished through automation. In the end, the world envisioned by Fresco and Joseph would be a sedentary one. No doubt, a sedentary population would prove to be more tractable and manageable for the ruling elite. Again, the “solutions” presented in Zeitgeist: Addendum would merely expedite humanity’s subjugation.

The Venus Project: An Experiment in World Technocratic Governance

At one point in Zeitgeist: Addendum, Fresco declares: “Patriotism, weapons, armies, navies… all of those are a sign that we are not civilized yet” (Zeitgeist: Addendum). Fresco’s condemnation of patriotism and his intentional juxtaposition of the concept with instruments of war echoes Wells’ contention in his work of normative fiction, The Shape of Things to Come: “The existence of independent sovereign states IS war, white or red, and only an elaborate mis-education blinded the world to this elementary fact” (The Shape of Things to Come).

To remedy the problems that he believes are rooted in the nation-state system, Fresco adopts the same solution presented by Wells:

“If you say large nations took land from smaller nations, used force of violence, you’ll get history talked about as corrupt behavior all the way along until the beginning of the civilized world. That’s when all the nations work together. World unification. Working toward common good for all human beings. And, without anyone being subservient to anyone else… without social stratification, whether it be technical elitism or any other kind of elitism…” (Zeitgeist: Addendum)

It is ironic that Fresco would present global government as an alternative to “technical elitism or any other kind of elitism.” A technical elite would be the natural correlative of a global machine state. If Fresco’s behaviorist conception of man is true, it stands to reason that the instantiation of a unified world would stipulate the primacy of those with behavioral “expertise.” Fresco’s emphasis on external forces as the dominant sculptors of human behavior provides the rationale for the necessity of a class of conditioners that would be unaccountable to the masses. Moreover, any form of global government is conceptually, politically, and economically predisposed to tyranny. Donald McAlvany explains:

A world government, by its highly centralized nature, would be socialistic; would be accompanied by redistribution of wealth; strict regimentation; and would incorporate severe limitations on freedom of movement, freedom of worship, private property rights, free speech, the right to publish, and other basic freedoms. (287)

Again, it becomes painfully apparent that the “solutions” proffered by Joseph and Fresco are not solutions at all. The Venus Project would merely install another form of scientific dictatorship. At one point in Zeitgeist: Addendum, two hands come into frame and connect to form a pyramid. In the center of the hands’ pyramidal configurations is the sun. The image bears an iconic similarity to the All Seeing Eye astride the truncated pyramid. Of course, this symbol held esoteric significance for many secret revolutionary organizations, particularly the Bavarian Illuminati. At this juncture, it is appropriate to recall the words of Hoffman:

The doctrine of man playing god reaches its nadir in the philosophy of scientism which makes possible the complete mental, spiritual and physical enslavement of mankind through technologies such as satellite and computer surveillance; a state of affairs symbolized by the “All Seeing Eye” above the unfinished pyramid on the U.S. one dollar bill. (50)

The Venus Project is but one more incarnation of the same sociopolitical Utopian aspiration: world technocratic governance.

A Cinematic Meme

Defenders of Zeitgeist: Addendum consistently parrot the impotent mantra: “It doesn’t matter if the film is correct. The point of the movie is to make you think.” First of all, this is tantamount to saying, “Truth is irrelevant.” Secondly, thought for thought’s sake is a fairly impotent activity, especially with humanity facing potential enslavement under a global government. Worse still, incorrect thinking can beget counterproductive and dangerous ideational entities. It should not be forgotten that communism, fascism, and other varieties of socialism were conceived within minds contaminated by dubious strains of thought. Zeitgeist: Addendum promotes ideational retrograde, a reality underscored by the dialectical commonalities between the film’s “solutions” and the problems that it ostensibly addresses.

Many Zeitgeist adherents fancy themselves as the enlightened possessors of open minds. This assessment is flatly bogus, as is evidenced by the Zeitgeist proponent’s refusal to give their assent to Christianity, patriotism, or free market capitalism. Moreover, the possession of a so-called “open mind” does not automatically qualify as a virtue.

G.K. Chesterton once wrote: “Merely having an open mind is nothing. The object of opening the mind, as of opening the mouth, is to shut it again on something solid.”

It would behoove the proselytes of Zeitgeist: Addendum to examine exactly what they are shutting their minds on. Same thing, for Keshe Foundation ones, that should consider values and concepts, philosophy and technological innovations as viewed from a sociological point of view, whilst we are again, trying to effect society through our actions, introducing a mixture of simple elements that will give birth to sub stantial changes.

This work is not aimed to criticize anyone in particular, but to understand absolute meaning of variables, vectors and inceptions, aimed to transform our society. To understand formulas used by innovators, means keeping an eye upon thinking, which is a mature way not to forget the mistakes we made in the past. Every time someone starts saying that he would like to change the entire world, accepting the possibility of interference within himself, we shall need to take care of the procedures this entity is proposing. When it is time, things happen naturally. Without the presence of the Force, efforts are useless, but some times, in so many ways, even if philantropists are wise men, structured world politics bend idealistic utopias into agendas, and this is of course totally gravitational, but we cant do much about it, if we are not aware of what is happening. We should never forget this is kali yuga. I had to point out all this, considering your possible lack of information, and time, to interconnect and study topics and matters that require a great deal of research. What you may call collective consciousness or interlinked awareness, since you did not point or write anything on this topic, ever, makes clear that even if one reaches, most, do not even care about what another conscience does or or find. Clones usually use an abuse, and seldom find out by themselves, or spend time to make things a little better. Clients, are not asked to think, but to buy. Consensus, needed to justify numbers, has nothing to do with harmonic laws and dharma, but is connected to plagiarism within democracies that are indeed totalitarian expressions of the self, and consequence of a mental illness. So, we should always take care if anyone becomes so arrogant as to claim that he could do this and that bad action against someone else. No nobility comes from this behaviour. Our horizon should reach the dimension of our sight. Beyond it, we should never try to change the position of a single leaf, because nature, is not obligation and option, but harmonic interplay. Will and wishes that are most of the time Ego shaped, will serve those who ask for more, and are here to abuse and not to serve.

Jedi Simon Datamining research work.

Sources Cited

Akin, William E. Technocracy and the American Dream: The Technocrat Movement, 1900-1941. Berkeley and Los Angeles: California UP, 1977.

Baker, Jeffrey. Cheque Mate: The Game of Princes. Springdale, PA: Whitaker House, 1995.

Bainbridge, William Sims. “Religions for a Galactic Civilization.” Excerpted from Science Fiction and Space Futures, edited by Eugene M. Emme. San Diego: American Astronautical Society, pages 187-201, 1982.

Billington, James H. Fire in the Minds of Men: Origins of the Revolutionary Faith. New York: Basic, 1980.

de Hoyos, Linda. “The Enlightenment’s Crusade Against Reason.” American Almanac 8 Feb. 1993.

Durrani, Noni. “Jacque Fresco On The Future.” Forbes.com 15 Oct. 2007

Fischer, Frank. Technocracy and the Politics of Expertise. Newbury Park, California: Sage Publications, 1990.

Goeringer, Conrad. “The Enlightenment, Freemasonry, and the Illuminati.” American Atheists 2006.

Hoffman, Michael. Secret Societies and Psychological Warfare. Coeur d’Alene, Idaho: Independent History & Research, 2001.

Howard, Michael. The Occult Conspiracy: Secret Societies–Their Influence and Power in World History. Vermont: Destiny Books, 1989.

Huxley, Aldous. Brave New World Revisited. Bantam Books, New York 1958.

“Jacque, Fresco.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. 21 November 2008

Jones, E. Michael. Libido Dominandi: Sexual Liberation and Political Control. South Bend, Indiana: St. Augustine’s Press, 2000.

Lewis, C.S. Christian Reflections. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1967.

Loeb, Harold. Life in a Technocracy. New York: Viking Press, 1933.

“Lucifer.” Answers.com

Martin, Malachi. The Keys of this Blood. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991.

McAlvany, Donald S. Toward a New World Order. Phoenix, AZ: Western Pacific Publishing Co., 1992.

Newman, J.R. What is Science? New York: Simon and Schuster, 1955.

Pike, Albert. Morals and Dogma. 1871. Richmond, Virginia: L.H. Jenkins, Inc., 1942.

Rand, Ayn. Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal. New York: Signet Books, 1967.

Raschke, Carl A. The Interruption of Eternity: Modern Gnosticism and the Origins of the New Religious Consciousness. Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1980.

“Scientific Socialism.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia 5 November 2007

Skinner, B.F. Beyond Freedom and Dignity. New York: Bantam Books, 1972.

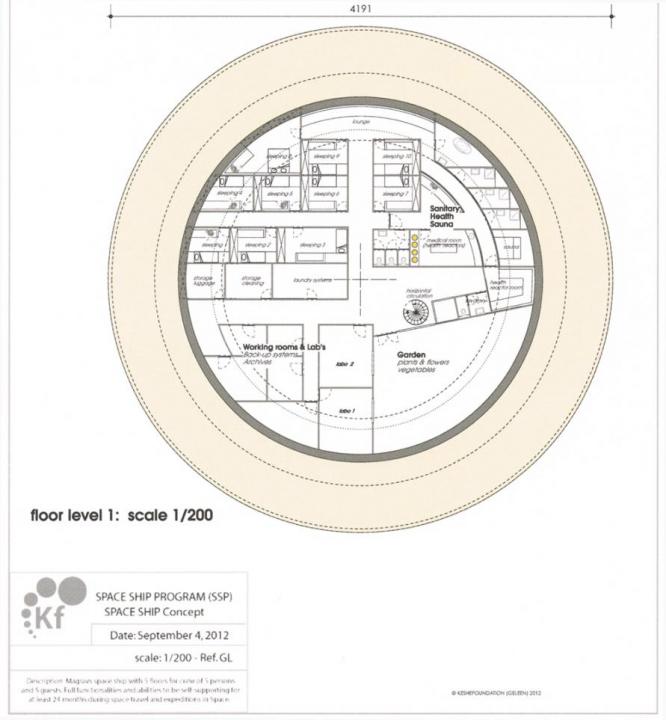

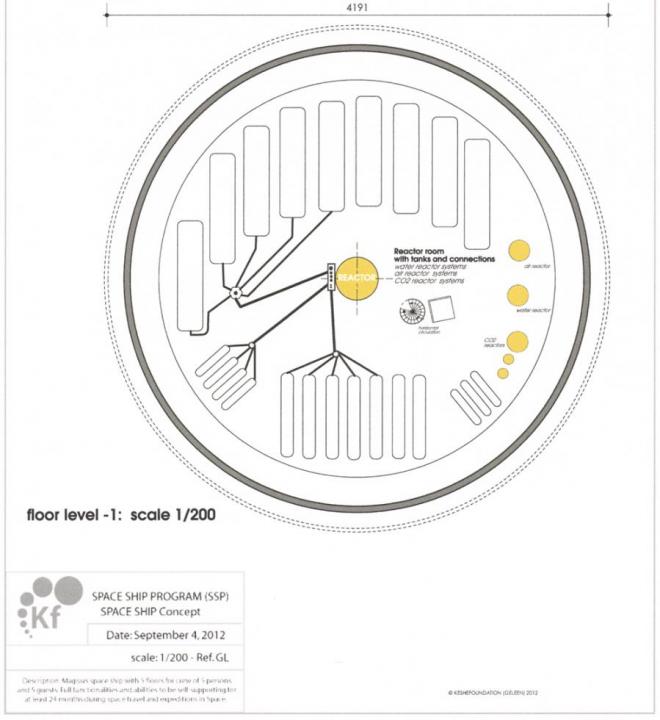

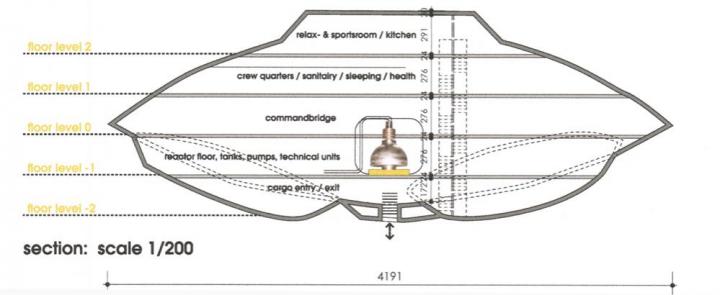

Understanding spaceship design from 224th KSW

Understanding spaceship design from 224th KSW